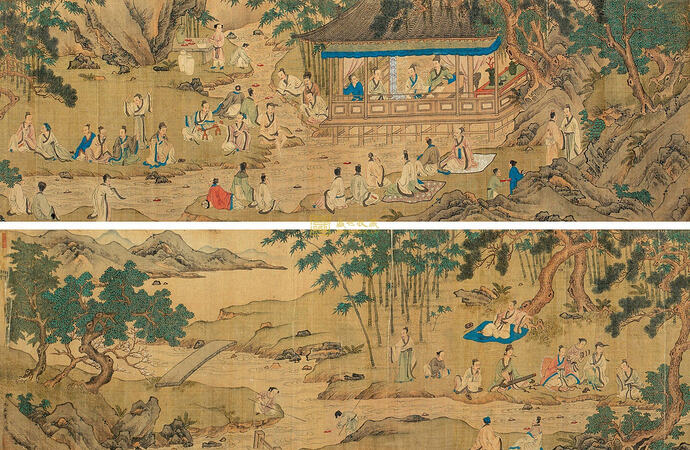

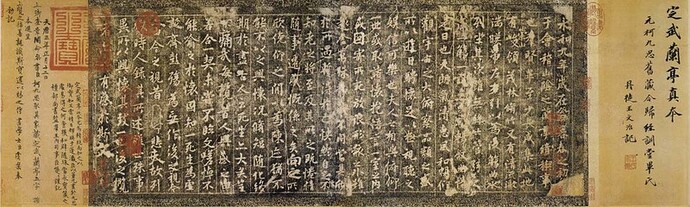

A time-traveling conversation the great calligrapher beautifully struck up with thinking posterity, on such serious topics as the infiniteness of the universe and the abundant contents of nature; the passing of time, or the coming of old age, which a man in a state of contentedness will easily become unconscious of; the change in one’s outlook on life as he develops in the world and interacts with the inhabitants thereof; human beings’ mortality and their inescapable fall into nothingness after death; the meaning of life and death; the common feelings, of people of the past, present and future, about life … The old festival tradition of floating spirits-filled goblets down a meandering brook and a partaker drinking from the one that stopped at their seat refreshingly beckons to modern people enslaved by mind-fettering technologies.

Incidentally, Lin Yutang’s own English writings merit praise, but his translations, mostly of the Chinese classics, are hardly a good read. He simply renders a Chinese text into English, but leaves behind its soul—the spirit of the Chinese people—in the process. It’s like a human being’s bodily flesh was well preserved, but his immortal elements, the mind, memory, personality and all, were lost. This short prose composition by Wang Shichih of China’s Eastern Jin dynasty isn’t so much a gay travel record as a profound philosophical thought gradually shaped as time elapses. Lin’s translation, however, strikes readers as no more than a plain account of what a group of forty-one people, a “goodly mixture of young and old”, did on an outing in late spring, and Wang’s sober perceptions of life and death, what he really wanted to convey in the introduction to his traveling companions’ works, are completely lost in translation.