Strictures on a Great Bard’s Visceral Sentimentality

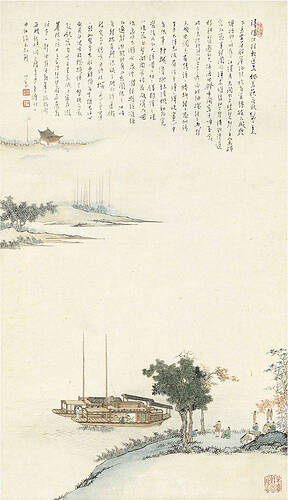

To be honest, this pipa lady doesn’t have a claim on our pity, and Po Chuyi’s weepy lamentation (his “black gown was wet” in the end) for her “misfortunes” is terribly misplaced. Po’s recent demotion from a higher position in the court had apparently rendered him wallowing in subconscious self-pity, to the extent that the poet would be helplessly diverted from being rational to being sentimental whenever he was pitched into an atmosphere full of pathos, like an autumnal moonlit night when he had to send a friend off in a solidary boat, all present tipsy and missing music. That’s the occasion in honor of which Po put his thought in verse.

From the instrumentalist’s impromptu autobiography, she was born in the empire’s capital and grew up in applause, extravagance, and vanity. Her early happiness and pride were derived solely from her “youthful glamor”, without an ounce from spiritual strength or intellect, which truly defines the value of a human being. It was merely for this outer form that those rich stage-door Johnnies from the local gentry would shower her with presents.

As she had lost this short-lived glamor in her thirties, however, the world in her eyes turned into an entirely different color: admirers walked away; carriages ceased to stay. Deprived of the former spotlight, the woman felt ignored and lonely—she wasn’t the intellectual type of Li Qingzhao who relishes solitude after all—and was being cynical about her husband’s entrepreneurship: she thought of her merchant husband as one who regards self-interest as more important than the marital bond. But how her man would have, as the saying goes, put a roof over her head and food in her stomach if he hadn’t gone to do business and “buy tea”? Shouldn’t she have been content and grateful to marry such a man of enterprise? This pipa lady had a more than decent life already, but still “sometimes cried herself to sleep”. The problem was in nothing but herself. Instead of turning mellow as she aged, the thirty-year-old stubbornly reminisced about the past and still wanted to remain young and radiant with that “youthful glamor”. She shouldn’t have blamed her current situation on the harsh vicissitudes of life. What had snatched the sense of peacefulness away from the pipa virtuoso was her incorrigible habit of resorting to her outer shell and never to her inner core, where the soul truly resides. Nothing of this washed-up has-been is deserving of Po’s poetic sighs, and it’s embarrassing to see our preeminent bard expressing empathy wholeheartedly for a superficial woman, just one of his myriad fellow “travelers in this wide world who hadn’t met each other before”.